On the Origin & Importance of Small & Fugitive Pieces

The Black World Today

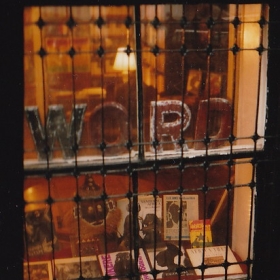

Harlem, New York

I’ve recently read, with great interest, that the African American Literature section of the Borders Books store at the Stonecrest mall in Lithonia, Ga, is suffering a pestilence of “pornography for black women.” The earnest author, most recently of A Love Story, Nick Chiles reports to the New York Times:

“What I saw there thoroughly embarrassed and disgusted me. On shelf after shelf, in bookcase after bookcase, all that I could see was lurid book jackets displaying all forms of brown flesh, usually half-naked and in some erotic pose, often accompanied by guns and other symbols of criminal life. I felt as if I was walking into a pornography shop, except in this case the smut is being produced by and for my people, and it is called “literature.”

Street literature, “ghetto fiction” as Mr. Chiles condescendingly calls it, is and always has been about sex, money and style. Immodest subjects, perhaps, but literature all the same. The English novel comes out of a street literature. The writers of the paperbacks for sale on 125th Street put Pamela in the projects, Moll Flanders on the stroll, and pit Tom Jones against The Man. Today’s provocateurs share with the canon’s Defoe and Richardson an enthusiasm for that same ever new concept, the written word.

As Samuel Johnson observed of the importance of the analogous literature of his times: “The mind, once let loose to enquiry, and suffered to operate without restraint, necessarily deviates into peculiar opinions and wanders new tracks, where she is indeed sometimes lost in a labyrinth, from which she cannot return and scarce knows how to proceed; yet, sometimes makes useful discoveries, or finds out nearer paths to knowledge.”

The language commandeered by the street writers has that jazz vernacular, that reducing of the don’ts into the doings of some kind, that seems intuitively in touch with language’s ability to shine. As the best jazz singers seem most comfortable in a limited range, some of these authors turn their limited vocabularies to great advantage. Colloquial, racy with simplicity and full of the humor of the average guy, these writers are closer in style to rap and hip hop musicians than to the university trained novelists.

Like their Elizabethan precedents, they write to entertain us common folk, who I see reading them on the subway. I asked a lady on her way uptown home from work, ‘How you like that book?’ As people like to talk about books, and I am a neighborhood bookseller, we talked about the “smut” she was into. She buys them in the neighborhood, swaps them with her girlfriends, reads them “for fun,” and sold me on reading the second volume of Thugs and the Women Who Love Them. “Good as sass,” was her estimation. I wish somebody would say that about my book.

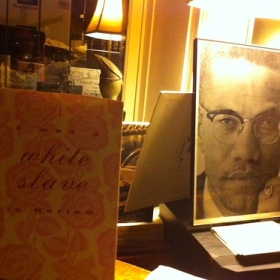

Reading one book lead to another and cultivates a new reader. Far from causing “Ralph Ellison to cringe into a dusty corner,” street lit’s vernacular retellings of The Invisible Man bring him to an audience that hasn’t read it in school. Many of these books were written in jail or in rehab. They have a story to tell and, unbeknownst to them, use old oral story telling techniques, African and English, preceding writing.

Liberated, they’ve got a manuscript and a dream. Ill-educated – in both the street and the academic senses – and with an infinitely small chance of making it through a “literary” agent’s slush pile, they take the means of production into their own hands. You want to tell your story you self publish, market and distribute the book. Printing a paperback novel might cost $2. At retail you can get $14.95. Selling them cheap to the Senegalese guy who puts them on the street, the author gets the money instead of the publisher or the distributor.

One shouldn’t be surprised if their printing costs have laundered some money but when you are not good for a loan and you want to publish your book, what are you going to do? Taking thoughts and making them tangible is risky business. Socrates argued against writing poetry down. Kids in Harlem wear t-shirts admonishing others not to tell. It depends on what you don’t want caught.

But what if you want to get caught? Uptown eloquence is elegance. You put it over and you get a rep. When you sell a sufficient number of copies, the publishers and the distributors downtown buy you out and you’re up. That your works are showing up suburban Atlanta is a measure of their commercial and personal success. The prestige of authorship trumps whatever you had to live down and celebrates you. You’re in the suburban chains, arousing prurient interest and tweaking the prigs.

“This noble profession,” says noble professor Nick Chiles, ” …has been reduced by the greed of the publishing industry and the ways of the American marketplace to a tasteless collection of pornography.”

Appealing to the lowest common denominator is nothing new in publishing. As pop culture’s morphed into mass culture, the box stores and the internet forced the independents out of business and formerly independent publishers were folded into mass media corporations. Having lost their independence, booksellers and editors learned to dumb it down from the marketing and accounting departments. For the past fifteen years we have been losing our independents and our books are in chains.

Recent statistics on literacy in the United States are not encouraging. Reading comprehension, literacy itself, among affluent whites is taking a dive. Curiously the only segment of our society in which the literacy numbers are up is in the African American community. What’s up with that, you say? Other studies show African Americans don’t buy much in the chains and stick with the neighborhood dealers they know and know them, buying on personal recommendation. They like to talk about books.

Towards furthering our independence, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and Daniel Webster differentiated American from the King’s rule-riddled English, lauding the vernacular. Their democratic ideals were such that Ebonics are less a blemish on than a triumph of our language. We don’t want rules for the sake of having rules. When the street talks, listen.

There’s a teenaged boy I know sells reefer on the corner who wandered off the street into my shop one day and lit up – not a smoke – “Whoa, man, this is dope,” – not meaning drugs – “I like to read.” He’d read some Donald Goines and Iceberg Slim and went away with a Chester Himes. I’m stringing him along. Next time I’m going to get him on the hard stuff.

© 2006 New York Press

Close Window