Pimpnology

Posted by admin on Sunday, December 24, 2006 · Leave a Comment

Pimpnology: Regarding Players, Hoes, Johns & The Life

Capitalism 101: Urban anthropologists Christina and Richard Milner’s keen street ecology,

Black Players: The Secret World of Black Pimps (Little, Brown and Co., 1972), laid out the game as played by what, in the early 70s, was commonly referred to as T

he System. In

The System, “Each player or actor is drawn to his particular role according to the needs of his personality, as well as the circumstances in which he finds himself,” and everybody plays the fool.

“Police, politicians, businessmen, lawyers, dope dealers, prostitutes, pimps – all are dependent on one another, yet all prey on one another. In modern urban life, none of us is immune to this kind of social network; the very life of the city is made up of such networks. Sociologists and pimp philosophers agree: it is like a gigantic game in which individual players may enter, leave, or change sides, but the game goes on, the structure persists, the pattern remains, and the cash flows back and forth as a symbol of the exchanges which are constantly taking place.”

The Milners’ commendable (and now out-of-print) study drew on some of the first written sources of this oral culture of laissez-faire savage capitalism. In it

The Life is a choice and one plays at it, in contrast to

The Game, in which one is played – a kind of residual from the days of the slave trade. There are essentially

The Players and

The Played, and what distinguishes those in

The Life from those in

The Game is recognition of certain fundamentals; primarily, that it is better to receive than to give. It is dishonest to pretend this formula for success is otherwise anywhere in the modern world. The Player knows the screwing the Played is getting is not worth the screwing he’s getting.

The Player knows

The Game is rigged and plays it to his advantage.

As The Life is played in

The Life: The Lore and Folk Poetry of the Black Hustler (University of Philadelphia Press, 1976):

You forget the quote that the Christians wroteAbout honesty and fair play

For you can’t live sweet not knowing how to cheat;

The Game don’t play that way.

This is no less true now than it was then. Hence this annotated bibliography of the literature growing from the experience and study of Pimpnology.

One of street literature’s great subjects has always been the highlife player, the honky-tonk man; the big-dicked, bejeweled raconteur/entrepreneur, no nonsense, old s’cool of hard knocks connoisseur of cunny; the pimp with the plan to stick it to

The Man. Chester Himes, Donald Goines and Iceberg Slim all postulated invincible rake potentates dedicated to the dubious proposition that pimps are smarter than their whores but, as Nelson Algren put it in

The Last Carousel’s “Watch Out for Daddy" things are not always as expected: “It wasn’t my Little Daddy that made a whore out of me. It was me made a pimp out of my Little Daddy.”

Fab 5 Freddy Braithwaite offered an eloquent explanation of this phenomenon in Darius James’

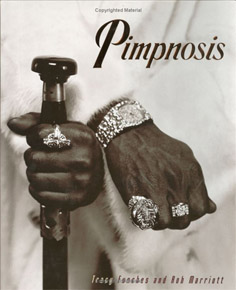

That’s Blaxploitation! (St. Martin’s Press, 1995) and I was reminded of Fab while reading the book-length photo essay,

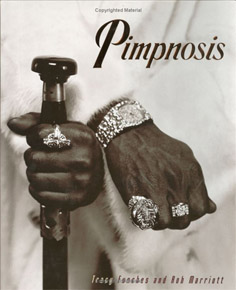

Pimpnosis, by Tracy Funches and Rob Marriott (HarperEntertainment, 176 pages, $34.95), wherein the MC of the Player’s Ball takes the mic cued to Willie Hutch’s “I Choose You” and riffs over it:

“The essence of the pimp game is a mental game. It’s a mental chess game not played against women but with women. A lot of people who have negative views on this lifestyle fail to realize that it is a chosen lifestyle. That’s why it’s called The Life: those who are in it choose to live that way. When a woman wants to be with a pimp, she has to choose him. And she has to choose him with a certain amount of money based on the status or level of the Game.”

Funches and Marriott spent two years interviewing and photographing pimps and players and hoze for

Pimpnosis. At the heart of

Pimpnosis is the symbiosis that distinguishes the player from the tricks, the parasites, the johns and the junkies.

“Junkies, man. They made me what I am-which is one very rich man. That’s all a trick is, is a junky. He just done fallen for pussy stead of blow, that’s all,” explains the sagely King Sugar Charmaine. “Every man has to fight the bondage of being like everybody else, and I beat that one right at the start. But then I also had to break free of the bondage of being turned out on my own shit.” There are the addictions to drugs, sex, money and power, to controlling other people by having power over them. “Addiction,” the King explains to the new fish, “is the central nervous system of what we call

The Life; addiction can be the pimp’s best friend – so long as it ain’t his own!”

In

Pimpnosis’ socio/sexual/economic equation, “…pimps are not a weird aberration of our social fabric – they’re the logical extension of the status quo.” The commensalism of pimps and whores places them as Players of the Played, but not above the ravages of the social equation.

The Life, Player wisdom has it, accepts suffering as the price of vice. It is what you get for choosing money over love. Many do.

The Life is about hunting in

The Game. Playing

The Game, “You may not be spreading your legs, or walking the streets, but you’re getting screwed. At least, you say, you’re getting paid for it. Guess what that makes you… There’s always someone making a profit on your hard work – and taking the lion’s share of the credit and the proceeds. Guess what that makes them.”

“If I can’t sell it, I’ll sit on it. I just won’t give it away,” was how Algren’s hoe explained

The Life. And such was the wisdom found in of the late-60s pulp literature by Iceberg Slim (Robert Beck) and Donald Goines I’d bought off the wire rack of the Greyhound bus station, published by L.A.’s Holloway House as a kid in khaki pants. What I was doing hanging around the bus station downtown had something to do with making teenage life worth living. The sole pimp I knew sold everything for the head in bed; his card read, “Hollywood Ike, Nature’s finest.” A similar musk to that lingering around Ike, whom I liked, hung in Iceberg Slim’s

Pimp: The Story of My Life (1969),

Airtight Willie and Me (1979) and

Mama Black Widow (1969). But Beck/Slim really snagged white folks like me with

Trick Baby: The Story of a White Negro (1967).

It wasn’t so much my wanting to be a Player but not wanting to be played that gave these books their appeal. They’re crime stories, and I have always been more interested in sin than not. Donald Goines’

Whoreson: The Story of a Ghetto Pimp (1972) had the same hard grasp of the vernacular that endears one to street literature and pop music. As a teenager, my mind was full of r&b and sin. Theology was a dance and the urban world was the stage. Writers who addressed my city and talked the talk were rapping on a soundscape of the Temptations, the Miracles, the never-smiling Miles.

Chester Himes presaged and transcended the genre. Like John Coltrane playing a Broadway show tune, his

Blind Man with a Pistol (1969) made as much out of the street’s theater as I’d ever been charmed by in print. And I’d been charmed. Susan Hall and Bob Adelman’s platinum-plated photo essay

Gentleman of Leisure (1972; also out of print) is an ancestor of

Pimpnosis, and it succeeded better than

Pimpnosis for being both closer in time and proximity to the Golden Age of American erotica – when the sexual revolution was being fought in the streets and the Cadillac was as synonymous with automotive splendor as the Benz is today. Adelman’s grainy b&w photos show the early-70s flared jeans and heels, the mini-skirted and booted hoe style appropriated by today’s yuppie princess.

It’s disappointing to compare today’s off-the-rack New Jack to yesterday’s fine, hand-tailored Prince of Darkness, if for no other reason than that pimps used to be worth looking to as arbiters of taste and splendor. One looked to the player’s urban sophistication for a grandeur that today’s over-sized saggity-assing falls far short of. Yesterday’s cultivated ponce looked stickpin sharp and lime-green tart-and was. If nothing else, one hopes a bit of the old-school couture the

Gentlemen of Leisure display would inspire higher sartorial awareness among today’s gangstas, who not only appear lax but are.

I am glad to have as part of my collection, but do not think so much of, recent titles from Research Associates School Times Publications. Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson’s

The Pimp’s Bible: The Sweet Science of Sin (2001) and Tariq “K-Flex” Nasheed’s

The Art of Mackin’ (2000). Both suffer from their authors’ being more exposed to syndicated tv talk shows than to actual crime syndicates. Like the artless “bachelor guides” to women once found in Nigerian market stalls, there’s a high quotient of humdingers to guffaw at. Just as "The Master of Life", the Nigerian author of

No Condition Is Permanent, several decades ago touted “24 charges against wives.” Nasheed’s

Art of Mackin’ features “20 Ways’ to tell if a Woman may be a Chickenhead (low-budget or hoochie)”. They both draw on a centuries-old tradition of violence and misogyny known to have been unhelpful. Nasheed painstakingly distinguishes the difference between the hoochie and the low-budget chickenhead (“that ‘fried chicken’ and ‘urine’ smell,” differentiating her from the homegirls and hoodrats), as if this were useful advice.

I think Nasheed also makes a great mistake in debunking the biggest misconceptions about pimps, as they are the very things that make the pimp’s profession interesting. In my adolescence, I enjoyed entertaining the idea of weasel-like pimps, dressed in loud, tasteless clothing, forcing satiable women into a sexual pay-as-you-go playpen that catered to whatever derivation on procreation my teenageness was into. But as Nasheed has it, it’s just a profession; a job as boring as a locker-room joke or softcore porn.

King Pimp Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson’s

The Pimp’s Bible at least makes pimping sound like a vocation. As riddled with lists of rules as

The Art of Mackin’, his prose styling is appreciably richer; it has the antiauthoritarian askance of quality Trickster narratives. That is to say, a pimp telling the Anansi the Spider or B’rer Rabbit stories gives greater satisfaction than a B’rer Bear pimp does, as the former is better at laying out than laying down the law. Gholson’s cellblock writer’s style doesn’t work well enough to wholly succeed, but the reader appreciates his try. Not all panderers can be patterers.

These are both self-helps that fall way short of their mark. They are no

The Game for Squares, Iceberg Slim’s unwritten but intended contribution to the genre, which promised to put the black on white and set the matter right. Closer in righteous spirit to the raw highlife tales of Nigeria’s Onitsha Market Literature is

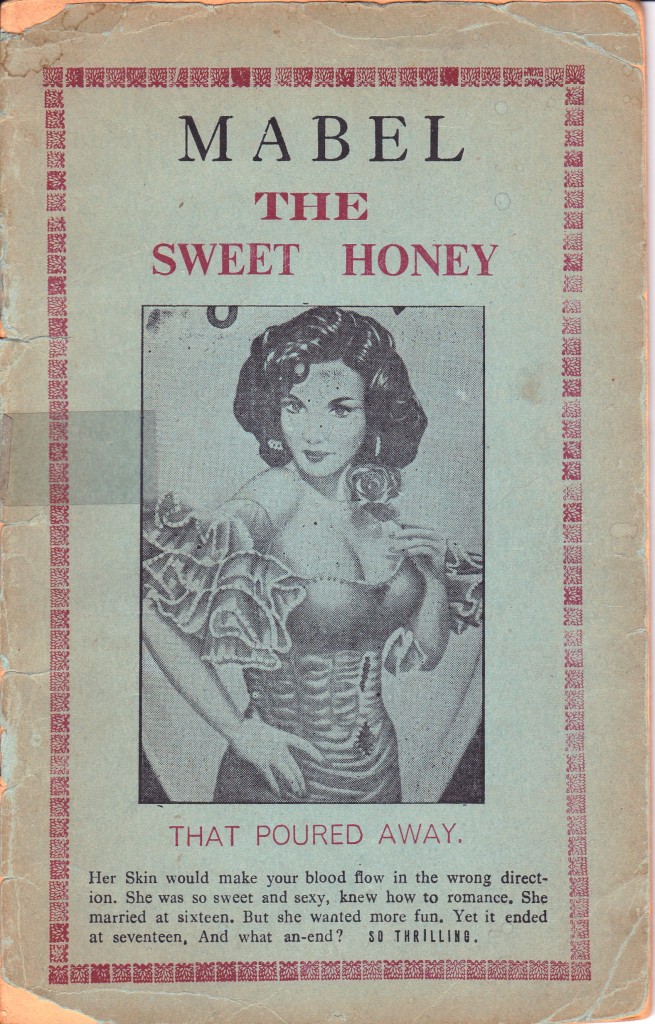

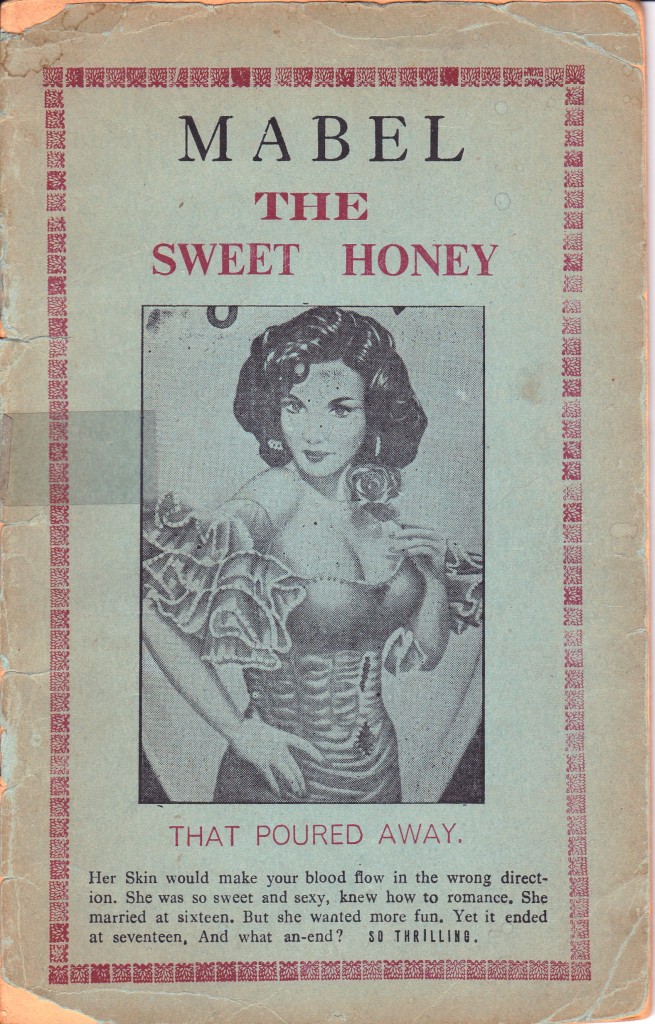

The Pimp’s Rap: A True Story, by Cincinnati’s Master Pimp (Old School, 1999). The Master Pimp’s first girl reminds me of the waitress in Speedy Eric’s

Mabel the Sweet Honey That Poured Away. Instead of working in a West African jungle juke joint, Master Pimp’s girl works at a Tad’s Steak House in LA. In fact, the book looks like an Onitsha production, although it isn’t a Nigerian-style chapbook, but a proper paperback. Both take promiscuity to the limit without really tantalizing, and neither is pornographic. They’re teases, really.

The Pimp’s Rap‘s idlest claim is to being “The First Rap Book!” Its greatest claim, however, which is in its first assured sentence – ”I will go on to write other great books but

The Pimp’s Rap was written by my soul” – isn’t wholly without merit, if vain. It is refreshing to hear from a guy who really loves his job. While no Boccaccio, Master Pimp sufficiently succeeds at evoking a boisterous Spenceresque braggadocio that sustained me to halfway through the book, when his pentameter imploded and I, for one, lost interest entirely. That was all the Master Pimp I could take. Critic and “Professional Model, Patricia Scott, Manhattan, New York,” quoted in the jacket copy, differs, and I defer to her firmer grasp of the subject than mine: “

The Pimp’s Rap is like discovering a hidden treasure. Filled with desires, fantasies and kinky sex, it made me hot and my panties wet!” I wish someone would say that about my book.

Even so,

The Pimp’s Rap lacks the elegance distinguishing

Pimpnosis, which looks like a Sotheby’s catalog. Photographer Funches double-mocha-sepia-toned spreads of costume jewelry, lingerie, champagne and Fleetwoods might be captioned “From the estate of a Gentleman of Leisure.” Pimpnology’s power dynamic is strong juju that plays on the primal desires that get us all into trouble. Sex, money and style are the real stuff of popular art, and there is no reason they’re any less the fundamentals today of new-schooled mass culture than they were in the 70s. They just seem to be. If the 21st century’s contributions to the literature mirrors

The Life today, it is all over but the posing. Today’s virtual misrepresentation in music videos prompts the response, as Marriott declares, that “too many lames attempt to claim the name and the fame but ain’t got the game” .

Pimpnosis is an attractively packaged homage to a venerable heritage. Marriott’s text illustrates the subject even better than Funches’ pictures. His homework must have been entertaining, because he tells the story that way. But no white girls!?! The union between a black man and a white woman used to be a revolutionary statement. Iceberg Slim and the pimps of

Gentleman of Leisure and

Black Players, were hip to the important role white women play in the game, but next to nothing much gets said about it in

Pimpnosis.

When my father would tell me the stories about how he saw the big pimps pulling their Cadillacs up to the welfare office to get their weekly checks-paid for by his tax dollars! – there was always a white whore and her politician john waiting in the car. Whores black and white, as elsewhere in life, get the short end in

Pimpnosis. Perhaps the book’s packagers are saving that material for the companion volume:

Whoritosis.

Kurt Thometz is the author/editor of Life Turns Man Up and Down: Highlife, Useful Advice and Mad English. (NY: Pantheon Books, 2001)

Volume 15, Issue 32

© 2006 New York Press

Funches and Marriott spent two years interviewing and photographing pimps and players and hoze for Pimpnosis. At the heart of Pimpnosis is the symbiosis that distinguishes the player from the tricks, the parasites, the johns and the junkies.

“Junkies, man. They made me what I am-which is one very rich man. That’s all a trick is, is a junky. He just done fallen for pussy stead of blow, that’s all,” explains the sagely King Sugar Charmaine. “Every man has to fight the bondage of being like everybody else, and I beat that one right at the start. But then I also had to break free of the bondage of being turned out on my own shit.” There are the addictions to drugs, sex, money and power, to controlling other people by having power over them. “Addiction,” the King explains to the new fish, “is the central nervous system of what we call The Life; addiction can be the pimp’s best friend – so long as it ain’t his own!”

In Pimpnosis’ socio/sexual/economic equation, “…pimps are not a weird aberration of our social fabric – they’re the logical extension of the status quo.” The commensalism of pimps and whores places them as Players of the Played, but not above the ravages of the social equation. The Life, Player wisdom has it, accepts suffering as the price of vice. It is what you get for choosing money over love. Many do. The Life is about hunting in The Game. Playing The Game, “You may not be spreading your legs, or walking the streets, but you’re getting screwed. At least, you say, you’re getting paid for it. Guess what that makes you… There’s always someone making a profit on your hard work – and taking the lion’s share of the credit and the proceeds. Guess what that makes them.”

“If I can’t sell it, I’ll sit on it. I just won’t give it away,” was how Algren’s hoe explained The Life. And such was the wisdom found in of the late-60s pulp literature by Iceberg Slim (Robert Beck) and Donald Goines I’d bought off the wire rack of the Greyhound bus station, published by L.A.’s Holloway House as a kid in khaki pants. What I was doing hanging around the bus station downtown had something to do with making teenage life worth living. The sole pimp I knew sold everything for the head in bed; his card read, “Hollywood Ike, Nature’s finest.” A similar musk to that lingering around Ike, whom I liked, hung in Iceberg Slim’s Pimp: The Story of My Life (1969), Airtight Willie and Me (1979) and Mama Black Widow (1969). But Beck/Slim really snagged white folks like me with Trick Baby: The Story of a White Negro (1967).

It wasn’t so much my wanting to be a Player but not wanting to be played that gave these books their appeal. They’re crime stories, and I have always been more interested in sin than not. Donald Goines’ Whoreson: The Story of a Ghetto Pimp (1972) had the same hard grasp of the vernacular that endears one to street literature and pop music. As a teenager, my mind was full of r&b and sin. Theology was a dance and the urban world was the stage. Writers who addressed my city and talked the talk were rapping on a soundscape of the Temptations, the Miracles, the never-smiling Miles.

Chester Himes presaged and transcended the genre. Like John Coltrane playing a Broadway show tune, his Blind Man with a Pistol (1969) made as much out of the street’s theater as I’d ever been charmed by in print. And I’d been charmed. Susan Hall and Bob Adelman’s platinum-plated photo essay Gentleman of Leisure (1972; also out of print) is an ancestor of Pimpnosis, and it succeeded better than Pimpnosis for being both closer in time and proximity to the Golden Age of American erotica – when the sexual revolution was being fought in the streets and the Cadillac was as synonymous with automotive splendor as the Benz is today. Adelman’s grainy b&w photos show the early-70s flared jeans and heels, the mini-skirted and booted hoe style appropriated by today’s yuppie princess.

It’s disappointing to compare today’s off-the-rack New Jack to yesterday’s fine, hand-tailored Prince of Darkness, if for no other reason than that pimps used to be worth looking to as arbiters of taste and splendor. One looked to the player’s urban sophistication for a grandeur that today’s over-sized saggity-assing falls far short of. Yesterday’s cultivated ponce looked stickpin sharp and lime-green tart-and was. If nothing else, one hopes a bit of the old-school couture the Gentlemen of Leisure display would inspire higher sartorial awareness among today’s gangstas, who not only appear lax but are.

I am glad to have as part of my collection, but do not think so much of, recent titles from Research Associates School Times Publications. Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson’s The Pimp’s Bible: The Sweet Science of Sin (2001) and Tariq “K-Flex” Nasheed’s The Art of Mackin’ (2000). Both suffer from their authors’ being more exposed to syndicated tv talk shows than to actual crime syndicates. Like the artless “bachelor guides” to women once found in Nigerian market stalls, there’s a high quotient of humdingers to guffaw at. Just as "The Master of Life", the Nigerian author of No Condition Is Permanent, several decades ago touted “24 charges against wives.” Nasheed’s Art of Mackin’ features “20 Ways’ to tell if a Woman may be a Chickenhead (low-budget or hoochie)”. They both draw on a centuries-old tradition of violence and misogyny known to have been unhelpful. Nasheed painstakingly distinguishes the difference between the hoochie and the low-budget chickenhead (“that ‘fried chicken’ and ‘urine’ smell,” differentiating her from the homegirls and hoodrats), as if this were useful advice.

I think Nasheed also makes a great mistake in debunking the biggest misconceptions about pimps, as they are the very things that make the pimp’s profession interesting. In my adolescence, I enjoyed entertaining the idea of weasel-like pimps, dressed in loud, tasteless clothing, forcing satiable women into a sexual pay-as-you-go playpen that catered to whatever derivation on procreation my teenageness was into. But as Nasheed has it, it’s just a profession; a job as boring as a locker-room joke or softcore porn.

King Pimp Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson’s The Pimp’s Bible at least makes pimping sound like a vocation. As riddled with lists of rules as The Art of Mackin’, his prose styling is appreciably richer; it has the antiauthoritarian askance of quality Trickster narratives. That is to say, a pimp telling the Anansi the Spider or B’rer Rabbit stories gives greater satisfaction than a B’rer Bear pimp does, as the former is better at laying out than laying down the law. Gholson’s cellblock writer’s style doesn’t work well enough to wholly succeed, but the reader appreciates his try. Not all panderers can be patterers.

Funches and Marriott spent two years interviewing and photographing pimps and players and hoze for Pimpnosis. At the heart of Pimpnosis is the symbiosis that distinguishes the player from the tricks, the parasites, the johns and the junkies.

“Junkies, man. They made me what I am-which is one very rich man. That’s all a trick is, is a junky. He just done fallen for pussy stead of blow, that’s all,” explains the sagely King Sugar Charmaine. “Every man has to fight the bondage of being like everybody else, and I beat that one right at the start. But then I also had to break free of the bondage of being turned out on my own shit.” There are the addictions to drugs, sex, money and power, to controlling other people by having power over them. “Addiction,” the King explains to the new fish, “is the central nervous system of what we call The Life; addiction can be the pimp’s best friend – so long as it ain’t his own!”

In Pimpnosis’ socio/sexual/economic equation, “…pimps are not a weird aberration of our social fabric – they’re the logical extension of the status quo.” The commensalism of pimps and whores places them as Players of the Played, but not above the ravages of the social equation. The Life, Player wisdom has it, accepts suffering as the price of vice. It is what you get for choosing money over love. Many do. The Life is about hunting in The Game. Playing The Game, “You may not be spreading your legs, or walking the streets, but you’re getting screwed. At least, you say, you’re getting paid for it. Guess what that makes you… There’s always someone making a profit on your hard work – and taking the lion’s share of the credit and the proceeds. Guess what that makes them.”

“If I can’t sell it, I’ll sit on it. I just won’t give it away,” was how Algren’s hoe explained The Life. And such was the wisdom found in of the late-60s pulp literature by Iceberg Slim (Robert Beck) and Donald Goines I’d bought off the wire rack of the Greyhound bus station, published by L.A.’s Holloway House as a kid in khaki pants. What I was doing hanging around the bus station downtown had something to do with making teenage life worth living. The sole pimp I knew sold everything for the head in bed; his card read, “Hollywood Ike, Nature’s finest.” A similar musk to that lingering around Ike, whom I liked, hung in Iceberg Slim’s Pimp: The Story of My Life (1969), Airtight Willie and Me (1979) and Mama Black Widow (1969). But Beck/Slim really snagged white folks like me with Trick Baby: The Story of a White Negro (1967).

It wasn’t so much my wanting to be a Player but not wanting to be played that gave these books their appeal. They’re crime stories, and I have always been more interested in sin than not. Donald Goines’ Whoreson: The Story of a Ghetto Pimp (1972) had the same hard grasp of the vernacular that endears one to street literature and pop music. As a teenager, my mind was full of r&b and sin. Theology was a dance and the urban world was the stage. Writers who addressed my city and talked the talk were rapping on a soundscape of the Temptations, the Miracles, the never-smiling Miles.

Chester Himes presaged and transcended the genre. Like John Coltrane playing a Broadway show tune, his Blind Man with a Pistol (1969) made as much out of the street’s theater as I’d ever been charmed by in print. And I’d been charmed. Susan Hall and Bob Adelman’s platinum-plated photo essay Gentleman of Leisure (1972; also out of print) is an ancestor of Pimpnosis, and it succeeded better than Pimpnosis for being both closer in time and proximity to the Golden Age of American erotica – when the sexual revolution was being fought in the streets and the Cadillac was as synonymous with automotive splendor as the Benz is today. Adelman’s grainy b&w photos show the early-70s flared jeans and heels, the mini-skirted and booted hoe style appropriated by today’s yuppie princess.

It’s disappointing to compare today’s off-the-rack New Jack to yesterday’s fine, hand-tailored Prince of Darkness, if for no other reason than that pimps used to be worth looking to as arbiters of taste and splendor. One looked to the player’s urban sophistication for a grandeur that today’s over-sized saggity-assing falls far short of. Yesterday’s cultivated ponce looked stickpin sharp and lime-green tart-and was. If nothing else, one hopes a bit of the old-school couture the Gentlemen of Leisure display would inspire higher sartorial awareness among today’s gangstas, who not only appear lax but are.

I am glad to have as part of my collection, but do not think so much of, recent titles from Research Associates School Times Publications. Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson’s The Pimp’s Bible: The Sweet Science of Sin (2001) and Tariq “K-Flex” Nasheed’s The Art of Mackin’ (2000). Both suffer from their authors’ being more exposed to syndicated tv talk shows than to actual crime syndicates. Like the artless “bachelor guides” to women once found in Nigerian market stalls, there’s a high quotient of humdingers to guffaw at. Just as "The Master of Life", the Nigerian author of No Condition Is Permanent, several decades ago touted “24 charges against wives.” Nasheed’s Art of Mackin’ features “20 Ways’ to tell if a Woman may be a Chickenhead (low-budget or hoochie)”. They both draw on a centuries-old tradition of violence and misogyny known to have been unhelpful. Nasheed painstakingly distinguishes the difference between the hoochie and the low-budget chickenhead (“that ‘fried chicken’ and ‘urine’ smell,” differentiating her from the homegirls and hoodrats), as if this were useful advice.

I think Nasheed also makes a great mistake in debunking the biggest misconceptions about pimps, as they are the very things that make the pimp’s profession interesting. In my adolescence, I enjoyed entertaining the idea of weasel-like pimps, dressed in loud, tasteless clothing, forcing satiable women into a sexual pay-as-you-go playpen that catered to whatever derivation on procreation my teenageness was into. But as Nasheed has it, it’s just a profession; a job as boring as a locker-room joke or softcore porn.

King Pimp Alfred “Bilbo” Gholson’s The Pimp’s Bible at least makes pimping sound like a vocation. As riddled with lists of rules as The Art of Mackin’, his prose styling is appreciably richer; it has the antiauthoritarian askance of quality Trickster narratives. That is to say, a pimp telling the Anansi the Spider or B’rer Rabbit stories gives greater satisfaction than a B’rer Bear pimp does, as the former is better at laying out than laying down the law. Gholson’s cellblock writer’s style doesn’t work well enough to wholly succeed, but the reader appreciates his try. Not all panderers can be patterers.

These are both self-helps that fall way short of their mark. They are no The Game for Squares, Iceberg Slim’s unwritten but intended contribution to the genre, which promised to put the black on white and set the matter right. Closer in righteous spirit to the raw highlife tales of Nigeria’s Onitsha Market Literature is The Pimp’s Rap: A True Story, by Cincinnati’s Master Pimp (Old School, 1999). The Master Pimp’s first girl reminds me of the waitress in Speedy Eric’s Mabel the Sweet Honey That Poured Away. Instead of working in a West African jungle juke joint, Master Pimp’s girl works at a Tad’s Steak House in LA. In fact, the book looks like an Onitsha production, although it isn’t a Nigerian-style chapbook, but a proper paperback. Both take promiscuity to the limit without really tantalizing, and neither is pornographic. They’re teases, really.

The Pimp’s Rap‘s idlest claim is to being “The First Rap Book!” Its greatest claim, however, which is in its first assured sentence – ”I will go on to write other great books but The Pimp’s Rap was written by my soul” – isn’t wholly without merit, if vain. It is refreshing to hear from a guy who really loves his job. While no Boccaccio, Master Pimp sufficiently succeeds at evoking a boisterous Spenceresque braggadocio that sustained me to halfway through the book, when his pentameter imploded and I, for one, lost interest entirely. That was all the Master Pimp I could take. Critic and “Professional Model, Patricia Scott, Manhattan, New York,” quoted in the jacket copy, differs, and I defer to her firmer grasp of the subject than mine: “The Pimp’s Rap is like discovering a hidden treasure. Filled with desires, fantasies and kinky sex, it made me hot and my panties wet!” I wish someone would say that about my book.

Even so, The Pimp’s Rap lacks the elegance distinguishing Pimpnosis, which looks like a Sotheby’s catalog. Photographer Funches double-mocha-sepia-toned spreads of costume jewelry, lingerie, champagne and Fleetwoods might be captioned “From the estate of a Gentleman of Leisure.” Pimpnology’s power dynamic is strong juju that plays on the primal desires that get us all into trouble. Sex, money and style are the real stuff of popular art, and there is no reason they’re any less the fundamentals today of new-schooled mass culture than they were in the 70s. They just seem to be. If the 21st century’s contributions to the literature mirrors The Life today, it is all over but the posing. Today’s virtual misrepresentation in music videos prompts the response, as Marriott declares, that “too many lames attempt to claim the name and the fame but ain’t got the game” .

Pimpnosis is an attractively packaged homage to a venerable heritage. Marriott’s text illustrates the subject even better than Funches’ pictures. His homework must have been entertaining, because he tells the story that way. But no white girls!?! The union between a black man and a white woman used to be a revolutionary statement. Iceberg Slim and the pimps of Gentleman of Leisure and Black Players, were hip to the important role white women play in the game, but next to nothing much gets said about it in Pimpnosis.

When my father would tell me the stories about how he saw the big pimps pulling their Cadillacs up to the welfare office to get their weekly checks-paid for by his tax dollars! – there was always a white whore and her politician john waiting in the car. Whores black and white, as elsewhere in life, get the short end in Pimpnosis. Perhaps the book’s packagers are saving that material for the companion volume: Whoritosis.

Kurt Thometz is the author/editor of Life Turns Man Up and Down: Highlife, Useful Advice and Mad English. (NY: Pantheon Books, 2001)

Volume 15, Issue 32

© 2006 New York Press

These are both self-helps that fall way short of their mark. They are no The Game for Squares, Iceberg Slim’s unwritten but intended contribution to the genre, which promised to put the black on white and set the matter right. Closer in righteous spirit to the raw highlife tales of Nigeria’s Onitsha Market Literature is The Pimp’s Rap: A True Story, by Cincinnati’s Master Pimp (Old School, 1999). The Master Pimp’s first girl reminds me of the waitress in Speedy Eric’s Mabel the Sweet Honey That Poured Away. Instead of working in a West African jungle juke joint, Master Pimp’s girl works at a Tad’s Steak House in LA. In fact, the book looks like an Onitsha production, although it isn’t a Nigerian-style chapbook, but a proper paperback. Both take promiscuity to the limit without really tantalizing, and neither is pornographic. They’re teases, really.

The Pimp’s Rap‘s idlest claim is to being “The First Rap Book!” Its greatest claim, however, which is in its first assured sentence – ”I will go on to write other great books but The Pimp’s Rap was written by my soul” – isn’t wholly without merit, if vain. It is refreshing to hear from a guy who really loves his job. While no Boccaccio, Master Pimp sufficiently succeeds at evoking a boisterous Spenceresque braggadocio that sustained me to halfway through the book, when his pentameter imploded and I, for one, lost interest entirely. That was all the Master Pimp I could take. Critic and “Professional Model, Patricia Scott, Manhattan, New York,” quoted in the jacket copy, differs, and I defer to her firmer grasp of the subject than mine: “The Pimp’s Rap is like discovering a hidden treasure. Filled with desires, fantasies and kinky sex, it made me hot and my panties wet!” I wish someone would say that about my book.

Even so, The Pimp’s Rap lacks the elegance distinguishing Pimpnosis, which looks like a Sotheby’s catalog. Photographer Funches double-mocha-sepia-toned spreads of costume jewelry, lingerie, champagne and Fleetwoods might be captioned “From the estate of a Gentleman of Leisure.” Pimpnology’s power dynamic is strong juju that plays on the primal desires that get us all into trouble. Sex, money and style are the real stuff of popular art, and there is no reason they’re any less the fundamentals today of new-schooled mass culture than they were in the 70s. They just seem to be. If the 21st century’s contributions to the literature mirrors The Life today, it is all over but the posing. Today’s virtual misrepresentation in music videos prompts the response, as Marriott declares, that “too many lames attempt to claim the name and the fame but ain’t got the game” .

Pimpnosis is an attractively packaged homage to a venerable heritage. Marriott’s text illustrates the subject even better than Funches’ pictures. His homework must have been entertaining, because he tells the story that way. But no white girls!?! The union between a black man and a white woman used to be a revolutionary statement. Iceberg Slim and the pimps of Gentleman of Leisure and Black Players, were hip to the important role white women play in the game, but next to nothing much gets said about it in Pimpnosis.

When my father would tell me the stories about how he saw the big pimps pulling their Cadillacs up to the welfare office to get their weekly checks-paid for by his tax dollars! – there was always a white whore and her politician john waiting in the car. Whores black and white, as elsewhere in life, get the short end in Pimpnosis. Perhaps the book’s packagers are saving that material for the companion volume: Whoritosis.

Kurt Thometz is the author/editor of Life Turns Man Up and Down: Highlife, Useful Advice and Mad English. (NY: Pantheon Books, 2001)

Volume 15, Issue 32

© 2006 New York Press