Chet Baker

Deep in a Dream By James Gavin

As Though I Had Wings By Chet Baker

At 3 a.m. on May 13, 1988, Chet Baker nodded out, threw himself out, or was thrown out of, a hotel room window in Amsterdam, quite as if he had wings.

Long ago and far away, I dreamed a dream one day: Sixteen years previous, a high school girlfriend of mine stole Chet Baker Sings and Plays with Bud Shank, Russ Freeman and Strings from a babysitting job because the William Claxton sleeve looked like a Valentine: Claxton’s b&w snapshots of California girls and surfers, the young Adonis trumpet player bulletin-board collaged with cupids, a red rose, the calling card of Miss Irene Paula Trivas, a telegram, Pacific Jazz letterhead, a push-pinned doily, a violets for your furs birthday greeting, all perfectly packaged to romance me and my druggy Miss. It’s been on my playlist of music to seduce by ever since.

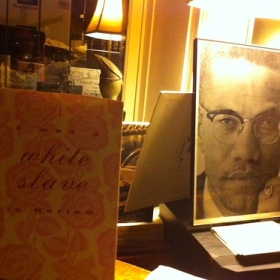

Baker’s “lost” memoir As Though I Had Wings, first published in ’97 and rereleased in paperback in ’99 (St. Martin’s, 128 pages, $9.95), was hardly his “real voice,” as the book’s copy would have it. That can still be best heard on recordings. Even his highly accessorized image-which wife Carol’s introduction discounts as a “one-dimensional caricature”-in Bruce Weber’s jive Let’s Get Lost does him greater justice than As Though I Had Wings. He barely scratches the surface of the high-life-and-hard-times genre of jazz autobiography when compared to Art Pepper’s or Anita O’Day’s books. Their attempts to write themselves through rehab were more successful. If anything, his attempt at telling his story shows him a willing accomplice to the “caricature” of the junkie jazz musician.

Who expected him to be able to write at all? Music in words is poetry and, with the possible exception of a prosaic ballad of a second chapter, not his métier. I expected even less. Something more along the line of, “Somewhere in this little book I will start to change my life and if that means anything to anybody good because I want to…” Music in words is poetry, and there’s a nice romantic little Baker pose where he makes a prosy stab at it: a stolen afternoon, a lake, a boat and a girl.

His persuasiveness doesn’t extend to the rest of the book, though, where stories trail off, go nowhere and dissipate in the chores of scores unmusical. Chet’s are the stock plots that attend all junkie journals. The addict’s life has the predictability of a humorless sitcom. Like television, it involves a lot of sitting around doing nothing. Like television, heroin has its charm in reducing all things to their lowest common denominator, riveting one’s attention to minor detail.

Without knowing his music, it’s unlikely anybody’d be seduced by Baker’s charm strictly by reading his memoir, or James Gavin’s newer biography, Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker (Knopf, 430 pages, $26.95), which I recommend to anyone considering drug addiction as a career move. Knowing the music, Gavin’s book does succeed in extending Baker’s enigma from the more seductive recordings through his pin-up boy good looks to the telling of his dire story, making it this summer’s substantial, abusive tar-beach read. Jazz on a Summer Day… You’ve driven this fine young thing with the top down up the Pacific Coast and the beach is yours. It’s the crepuscule and you got your nellie. You got the lubricants, social and otherwise. You get there and there’s a fire in the fireplace and you want something hipper than that Miami Beach thing Bobby Hackett’s got going with Jackie Gleason. Nothing too intellectual, but jazz as a soundtrack for its namesake, its synonymy with copulation. Nothing too funky. Chet comes on and you got the easy-sounding affluence that seduces: the privacy, the comfortable furniture, the MG, the sloop, the ice cream cone, the goatee, the tan, the top-siders, the bottom, all your favorite vices and devices. “Let’s get lost in a romantic mist/Let’s get crossed off everybody’s list…” Sheet music to drift off to lotus land.

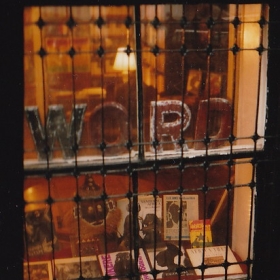

William Claxton’s 1955 book, Jazz West Coast, and the LPs of the same title, married the era’s music to a marketable bourgeois bohemian lifestyle, and no one looked or played the part so much as Chet Baker. Claxton’s photos made a significant contribution to Baker’s career from the start. He made “West Coast” as much a visual style as Baker contributed to its being an identifiable music style. The gentrified Ivy League weekend beatnik Playboy esthetic of the time appealed to a record-buying public who wanted to take five.

Much of the music associated with the style has enjoyed a revival as bachelor-pad or lounge music, but the better Baker lacks the kitsch that has somewhat frighteningly ceased to be ironic. Baker’s picture-perfectness decidedly added to the sound’s luster. Few of his contemporaries had the charismatic qualities the camera looks for and teenagers get the vapors over. Fewer still got kudos from both Charlie Parker and the record-buying public. As a musician he was less posed than poised. Seldom a superfluous note. Whether he was playing lugubriously intoxicated ballads, straight bell-clear bop or some fetishistic thrall with strings, there was scarcely a wrong note.

People who didn’t necessarily dig jazz dug Chet. Reputedly, Jayne Mansfield and Marilyn Monroe would sit at the front tables in the very intimate Wilshire district club, the Haig, where an 11-month stint with Gerry Mulligan’s infamous pianoless Quartet in ’53 brought him to the public eye. The Haig was where you went to hear the hip new sounds in brat-pack Hollywood. Mulligan’s Birth of the Cool middle register arrangements matched the sincerity and simplicity of Baker’s lyricism and relaxed the stringencies of modern jazz into a cinematic hybrid.

Chet and Gerry personified what would become known as the West Coast style. This misnomer was opposed to an equally simplistic definition of East Coast style as hard black bop. Previous to bebop, jazz had been popular, not art, music. Specifically, it was American popular music, catering to America’s particular and sometimes peculiar taste. To many this new intellectualized music didn’t serve its previous function. Jazz, as we all know, once meant sex, and sex, as we’ve all been told, should mean romance. If not romance, at least the illusion of romance. Wasn’t jazz, turned up just loud enough so the kids wouldn’t hear, something you could dance to as you turned on the charm that would get you there? Bebop seemed to defeat both purposes.

Baker’s melodic romanticism filled both purposes and a few more. The unmistakably androgynous timbre of his singing brought ambiguous meaning to “My Funny Valentine” (the Quartet’s hit) and “Do It the Hard Way.” “My Buddy” addressed an audience delightfully surprised at being catered to by a heterosexual white jazz man whose looks were compared to James Dean’s. Rex Reed characterized Baker’s singing as “an innocent sweetness that made girls fall right out of their saddle Oxfords.” Doug Ramsey said it was possessed of “the terminal vibrato without which singing cannot be jazz singing.” Romantic with a frankly sexual persuasion, Baker’s renowned lyricism bordered on the pornographic for some-an audience that hadn’t the slightest interest in jazz and quite possibly still doesn’t appreciate him as the accomplished jazz musician he was.

Jazz musicians and aficionados either loved him or dismissed him as a Miles wannabe. Some were put off by the androgyny. Baker cultivated the dangerous pretty-boy look, and his attitude drew a cult audience few of his contemporaries enjoyed. The inverted quality of the singer appealed to Others, cocktail ladies and gay men like Weber among them. Baker entered the pantheon of heroes all kinds of addicts turn to for justification. Despite, or perhaps because, the typical addict remains a middle-class wage-earner who lives in the suburbs, the stereotype remains romanticized. Artists, musicians, writers and theatrical people, for living public lives, have been the stereotype’s fodder, despite statistics to the contrary. These tragic/magic figures are worshipped for their ability to contradict their hazardous existences, to appeal to our sympathy, and in doing so make their mark on, and of, whoever will listen.

A few weeks after Baker’s death, Weber’s documentary Let’s Get Lost revived a career 30 years in decline. If Weber’s homoerotic esthetics doting on the cheekbones and fawning over the enfant terrible romanticism of one of jazz’s finest trumpeters and most charming singers was occasionally distasteful, I had to remind myself it was as much an homage to photographer Claxton as to the junkie/musician. The movie’s soundtrack, among Baker’s best later works, fully justified, to my mind, any bad influence this retelling of the heroin/heroine myth may have had on the beautiful and the damned who’ve made it the soundtrack of their own narcotic daze. For all the talk of Larry Clark’s Tulsa inspiring heroin chic, Weber’s styling of Claxton and Baker had as much effect. Some pretty overdosing while listening to Chet croon “Imagination” is not the music’s or the film’s fault but that of the ready availability of high-quality dangerous drugs. Heroin heroes don’t love anybody.

Junkie Mulligan’s personal antipathy to Baker had nothing to do with musicianship. Jealous? Undoubtedly. The Quartet’s instrumental hit, “My Funny Valentine,” was a vehicle for Baker, and the sideman was getting as much attention as, if not more than, the leader. Mulligan’s heroin addiction had him by the cojones at a time when the drug was still fondling his partner.

Their falling out smacks of a lovers’ spat that Baker won. Pissed? Justifiably. Baker and Gavin recount the bust that would bust up their affair and earned Mulligan some scathing contempt. While Mulligan did his time, he had a good brood over the Hermosa Beach pretty boy with the pug nose who had the girls, the boys, the cars, the dope and the recording contracts. In his absence, Dick Bock’s Pacific Jazz continued to record Baker with the pianist/songwriter Russ Freeman, and their first vocal records matched the enthusiastic response Mulligan’s Quartet enjoyed.

Previous to the posthumous movie and books, Chet’s reputation as a user, and not just of dope, seemed to preclude his regaining the popularity he’d enjoyed in his youth. Self-exiled from the States for the better part of three decades by junk, Baker still enjoyed some of the trappings of California cool in European settings more tolerant of his vice. Besides playing the swellegant supper clubs, he recorded two or three albums a year in Italy, France and Belgium. Oriana Fallaci wrote glowingly about him in L’Europeo. Dino DeLaurentiis signed him to write and perform the soundtrack to their screenplay of his la dolce vita scene.

The stories would sound as glamorous as much of the music he recorded there if they weren’t so sordid. The ’60-’61 Italian Riviera scandals, with the headlines reading, “Chet Baker Found in Gas Station Toilet,” sent the paparazzi chasing him and his Elizabeth Taylor-lookalike showgirl. It brought a spate of publicity that worked rather well for him, and a rather productive 16 months in the medieval tombs at Lucca. If possible he was a worse father than he was a junkie. One wonders his children didn’t disown him.

We don’t hear from the horse’s mouth about the ’66 drug deal that went wrong, when Baker got his teeth kicked in and later found himself reduced to pumping gas. The memoir peters out in ’63, by which time the man had joined the living dead. The music didn’t. Limelight, Prestige and World Pacific kept him recording, brilliantly paired with musicians like Hank Jones and Kirk Lightsey, or cynically paired with Bud Shank or the Mariachi Brass. For his ’74 comeback Dizzy Gillespie facilitated a Lee Konitz/Baker pairing and a Mulligan/Baker reunion at Carnegie Hall.

His discography lists more than 200 LPs and CDs, half of which were put out in the last 15 years. For any musician, this would be an accomplishment. The majority of these recordings, made in France, Italy, Holland, Denmark, points north and finally Germany, were as bad as his U.S. low points with the Mariachi Brass or the awful Blood, Chet and Tears. Before his passing and commemoration, few of these or any of his recordings were available in the U.S. His bins at the CD stores are now comparable in size to Louis Armstrong’s.

For a junkie prone to bottoming out on a fairly regular basis, such accomplishment is extraordinary. It’s what’s missing from both As If I Had Wings and Deep in a Dream. His widow Carol recalls in her intro to the former the “very essence of Chet’s life: unremitting chaos shot through with pure genius.” What’s missing here is the genius, now dead on the page, whereas the music still gets us to the essence.

Volume 15, Issue 27

© 2006 New York Press