On Collecting

Style reveals the man. The building of a library is an act of style, an expression of what we are and a good measure of who we are. Collecting is an act of self-realization. One collects books and builds a library to create an intensified environment. It is a philosophical statement as this room is a reflection of our perception of the world.

In well-appointed homes library space is precious and collections are highly prized reflections of the inhabitants interests, tastes, scope, and depth. In dicty sets Nancy Mitford’s writings are as de rigueur as chintz, Enid Bagnold’s autobiography still makes for after dinner conversation, and Proust, fraught with significance, read or unread, is an endless source of presumably refined speculation on society’s motivations and recreations.

Mystics and radicals read reveries towards revelations. Others, who flatter themselves realists, won’t sully their shelves with poetry, fiction or belles lettres. Science, history and politics adorn their studies in chronologically categorized epochs. Their highly specialized selections of technological tomes vie for linear footage in the stacks with the reference essential to the practical intellectual.

To attract a collector a book must appeal to the eye, the mind or the imagination. While it is an understatement to remind ourselves that a book is a visible act of communication and not just a thing, there is a need for truth that wants to know the origin of a thing in order to understand its nature. Books possess interiors much like the interiors of human beings.

“The most profound enchantment for the collector,” wrote Walter Benjamin, “is the locking of individual items within a magic circle in which they are fixed as the final thrill, the thrill of acquisition, passes over them.”

There are those who consider books as objects: curios for the connoisseurs of bindings, investments when they belong to limited editions or are illustrated by fine artists. The fine bindings of the 17th and 18th century bring high prices more often for their jackets than to their content. Collectors of modern literature place a great deal of importance on the condition of the dust jacket, a sensibility alien to their counterparts in the first half of the 20th century.

To many collectors, first editions possess a vital signature that justifies the time and expense involved in tracking down the illusive rarity. They have a symbolic validity that later editions just don’t possess and possession is the distinction between the bibliophile and the bibliomaniac.

Books’ appeal to the imagination are sometimes those which are interesting on account of their associations. The famous “Sentimental Library” Dr. Rosenback acquired from Harry B. Smith is an example of what I mean. It’s a great collection of conversation pieces: the Pickwick Dickens presented to his sister-in-law, Mary Hogarth, whose death postponed the publication of Part XV because of the author’s emotional collapse; the copy of Queen Mab Shelly gave to Mary Godwin inscribed, “You see, Mary, I have not forgotten you”; the copy of Shelly’s Adonais, bound in vellum, presented to Joseph Severn with one of Severn’s deathbed portraits of Keats pasted on the flyleaf.

One needn’t be a bookseller or a scholar for books to become a passion. Reading is a powerful drug that occupies the minds of the most profound and the most superficial. The passion that excites and allows bibliophiles to distinguish themselves is collection. It encourages ambition and flights of fancy discouraged in a society in which the spirit of enterprise is limited to the marketplace and ideas are provided by the media.

The library is a sanctuary immune from the anxieties of the office, the mediocrities of the media, the trials and tribulations of domesticity. Reading one book takes us out of range, away from the daily routine, away from petty, cloying, responsibilities. In a room full of books, insulated and absorbed, it becomes possible to sit quietly by oneself and want for nothing; the library itself becomes that finer world within the world all look for and few find.

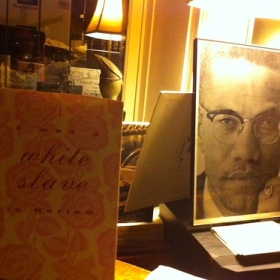

Image: Kurt Thometz cataloguing Mrs. Astor’s library, 1988, photographed for the New York Times piece: “Where to Find It: Taking the Chaos Out Of Home Libraries“.