“I Am Mad About Nigerian Literature …”

“I am mad about Nigerian literature”…says Kurt Thometz, American who sells Nigerian books in New York.

By HENRY AKUBUIRO (ifeanyi_mcdaniels@yahoo.com)

Lagos Sun, Sunday, February 19, 2006

The world is indebted to Harlem in New York, USA, for its contribution to world literature and art. The Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s was an epoch in American history that witnessed the blossoming of creativity by black Americans.

Literature was a key factor in the Harlem Renaissance, and it produced literary heavyweights, such as Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Countee Cullen in poetry, and Zora Neale Hurston and Nella Larson in prose.

For the African-Americans then, writing was an escape from the trials and tribulations of life. In art, the artist set out to establish an artistic community through improvisation and style, creating an iconography and thematic content that included Africa as a source of inspiration.

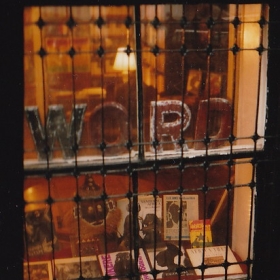

Once again, something spectacular is happening in Harlem. Unlike in many bookshops in Nigeria, where you cannot find the legendary Amos Tutuola’s books or his contemporaries, in Jumel Terrace Books, a bookshop located at West 160th Street in Harlem, New York, you are at home with Nigerian and African books, from Amos Tutuola to Chinua Achebe, Cyprian Ekwensi, J.P Clark, Wole Soyinka, Emmanuel Obiechina, Onitsha market literature, Uzodimma Iweala, Chris Abana, and what have you.

The wonder of it all is that it is not a certain Obi or Tunde that is selling the books; the man behind it all is a white American called Kurt Thometz, who happens to be an online fan of our literary page in Sunday Sun.

Kurt Thometz was born in St. Cloud, Minnesota, and was raised mostly in Hopkins, Minnesota. He came to New York in 1973 and has been a bookseller since. “Dealing books is like dealing dope,” he once said in an interview with New York Press. His mentor was William French of Greenwich Village’s University Place books, one of America’s earliest and preeminent bibliographers of African-American and African literature.

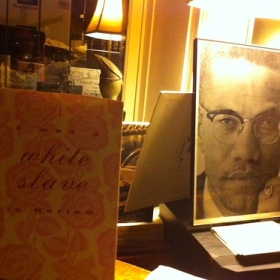

His discovery, in French’s shop from the late 70s into the 80s, of the popular Onitsha market literature, which thrived in Eastern Nigeria after World War II to the onset of Nigeria-Biafra War in the 1960s, awoke his curiosity about this literary phenomenon, and, in 1995, he wrote a pamphlet of his own catalogue of the literature entitled The important Book of Nigeria Market Literature. He followed it up with a 365-page book in 2001 entitled Life Turns Man Up and Down: High Life, Useful Advice, and Mad English. He also recalls that, as a young bookseller in Minnesota, Amos Tutuola had a great effect on him.

Thometz informs Sunday Sun online from his base in Harlem that he has never been to Nigeria, but literature knows no borders. “Unfortunately, I have never been to Nigeria, mine is a literary construct,” he says, adding, “as I write in Life Turns Man up and Down…, ‘neither a place a philosophy, nor so much a style but a dialectical touchstone, one that implied more than it ever explained.” The American bibliophile is a good acquaintance of the Nigerian novelist, Chinua Achebe, and holds him in high esteem.

He recalls excitedly that his first meeting with the legend was a watershed in his life. “Emmanuel Obiechena facilitated our meeting. When Achebe had read and liked my book, he invited my family and me to visit him at his home. The book was very well reviewed, but having Achebe tell me he liked my book was the highest praise imaginable to me. I am extremely flattered he teaches his West Africa Literature course with my book.”

To Thometz, the Noble Prize for Literature academy has been unfair to honour his literary idol. He says that Achebe’s Things Fall Apart ranks among the best books of the last century.

His words: “In my estimation, Things Fall Apart is no less than the most important novel of the second half of the 20th century but I don’t think it’s the prize he has his eyes on.” From his experience, the American audience likes reading Nigerian books, and he sells more of Chinua Achebe and Amos Tutuola’s book than any other. Achebe and Tutuola sell best, Cyprian Ekwensi follows and have won over several readers to Gabriel Okara.

The Voice (by Gabriel Okara) is underappreciated. Robert Farris Thomson’s writing on Yoruba culture’s influence in Bahia, Cuba, Haiti, Miami, and New York, The Flash of the Spirit, is on my best seller list,” he informs. Thometz has read some new generation Nigerian writers, like Chris Abana and Uzodimma Iweala, but says these are not enough for him to have a clear picture of the state of the art. “I am more interested in the state of literacy,” he admits.

In an article he wrote entitled “Things Falling Together” on Chinua Achebe, published in New York Press, after watching Achebe deliver a lecture at New York University’s Vanderbilt Hall on May 4, 2001, Thometz described Achebe as a man “who is arguably the greatest literary stylist of the second half of the 20th century and one of the very few truly wise people I have ever met… The more you read of and about him, the more respectful you become of his deportment, his stature, his cool, and above all his message … His reader gathers an egalitarian quotient from the timbre and tone of dry irony in the Igbo language, which underlies Achebe’s English literature and voice. It takes us back to the fundamentals, when words were magic, had mysterious powers, and what you wanted to happen could by your saying it. It is a praise song to print’s capacity to bring hidden wisdom within our grasps. Achebe reminds us things are not what they seem, and no condition is permanent.”

John Strausbaugh, writing in New York Press, said Kurt Thometz has a maniac for books. All over his house, even the kitchen is lined with scores of his wife’s cookbooks. What’s more: “His library reflects intelligence, idionsycractic taste and curiosity more than acquisitiveness. It’s the difference between a person who loves books and someone who just loves having them.” A private librarian, Thometz also earns a living helping his clients build and organize their collections.

Before he came to New York, Thometz was working in a bookstore outside Minneapolis when he met a poet from New York, Patti Smith, who advised him to come over. On his arrival, be berthed at the popular 4th Avenue, home to New York’s booksellers and antiquarians. Later on, he worked as a salesman and book scout at the expensive uptown Madison Avenue Bookshop for seventeen years.

He never study Library Science – in fact, he skipped college in transit. Our American hero is a product of self-education. Today, when he theorizes about African literature, he elicits great adulation from here and there. When Sunday Sun seeks his opinion on how Onitsha market literature, from an outsider’s perspective, contributed to our literary canon, he replies that, “with the possible exception of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, nothing shows the impact of Western urbanities’ technologically adroit Word on the ordinary African’s values than the chapbooks of the Onitsha writers … The Onitsha writers seem to precipitate a sudden interest in the field of letters and learning with the “Orality Problem”. Interest in the differences between oral and chirographic cultures, between the written and the spoken word, coincide with the pamphleteries’ discovery outside Nigeria in the early 1960s.”

Thometz posits that Walter Ong’s Orality and Literacy crystallizes the concepts Marshall McLuhan’s Gutenberg Galaxy and Jack Goody and Watt’s Essay “The Consequences of Literacy” address. These seminal works, he says, found their pretexts in Igbo land’s cross-cultural collision. McLuhan, he further says, refers repeatedly to West African literature exemplifying the premises of his Gutenberg galaxy.

The diction of Onitsha market literature, which he describes as “Mad English of Eastern Nigeria”, is its greatest appeal, because of its jazzy vernacular, or what he calls the “reducing of the don’ts into doings of some kind, that seems intuitively in touch with our language’s ability to revitalize itself”.

He explains further: “Dylan Thomas, who coined the term Young English in his review of Amos Tutuola’s Palm Wine Drinkard, once described poetry as ‘the rhythmic, inevitably narrative movement from an underclothed blindness to a naked vision’. Herein, for me his key to these writings and their appeal to an audience that has no interest in this literature as African. These writings and their appeal transcend the experience in which they are rooted and speak a language that, while sometimes audacious, is easily understood by its poetic justice.”

A visit to Thometz’s website jumelterracebooks.com would reveal the American as a man with cosmopolitan outlook to life, something of bookish enigma that you cannot but slavishly admire. Obviously, he is tantalized by the phenomenal Onitsha market literature and has even mooted the idea of making a documentary out of it. As John Strausburg once reported, “He ‘ll play Les Blank to their Werner Herzog”. Fancy that! Apart from that, he is nursing the idea of compilling copies of the now rested popular Black Orpheus art magazine published by Ulli Beier in Ibadan many years ago in another book, and many more.

The marvel of this man is that, in these days of globalization, when many Africans are quick to jettison their Africanness, a certain Kurt Thometz, a white – not black –American, is out there in the most powerful nation in the world canonizing our literary and cultural heritage. Let’s ponder on this Thometzian truism for a while: “The history of colonialism is as much about the triumph of the literate over the illiterate than it is about any racial or national superiority”.

What do you make of it?

Chinua Achebe wrote Things Fall Apart primarily as an apmtett to dispel the colonial stereotypes of African culture—as barbaric and morally inferior to European culture—fostered by colonial literature such as Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness and Joyce Cary’s Mister Johnson. Achebe sees the continued existence of these stereotypes as a result of the Western world’s ignorance of the real and rich African culture. Thus, in his novel, he sets out to portray his native Igbo culture as the culturally rich and socially complex culture it really is. Achebe, however, refuses to fall victim to writer’s bias, the same bias he had criticized in Conrad and Cary’s portrayal of African culture. To that end, Achebe depicts the Igbo tribe with realism and neutrality; he does so by describing both the positive and negative aspects of the society, such as its treatment of women, which is in some ways better than that in Europe and in others, worse. Though he does generalize and describe the arrival of European missionaries as the negative catalyst that brought about the destruction of Igbo culture, Achebe still manages to elude bias in his depiction of the Christian missionaries. The calculating and ruthless Reverend Smith and the District Commissioner are contrasted with the polite and respectful Mr. Brown who is revered by the Igbo leaders for being tolerant enough to engage in religious discussions with Akunna and learn about the Igbo theological system. Instead of forcing down his opinions of African culture on the reader or arguing vehemently for African superiority like other Western colonial writers did, Achebe merely communicates an image of Igbo culture with all its complexities and rich history. By the end of the novel, the reader, fully aware of Igbo traditions, cannot help but feel sympathy towards the flawed Igbo culture and the novel’s protagonist, Okonkwo, and anger towards the European missionaries and their pretentious declarations that the Igbo community should be replaced by a superior Christian brotherhood. There, I believe, lies Achebe’s greatest success.