The Book Problem

Were the problem book people like us, it would soon go away. It is not our weaknesses, or our sentimentality, or our nostalgia. It’s As If’ we’ve become obsolete and we haven’t. By ‘we,’ I mean We the People of the book: Jews, Christians, Islamic people and a lot of people who believe what they want.

The problem has to do with the consequences of post-print literacy. Technology has its self-serving agenda of efficiencies that, harnessed to a savage capitalism, turns out to be in the interest of the few. Post-Literacy is pixilation. We are being pixilated and there are ulterior motives that haven’t our best interests in mind. As all fine artists know, the difference between the way we comprehend the printed and the electronic word is the difference between a Van Gogh on line and a Van Gogh on canvas. As all poet’s know, it’s what’s lost in translation. To lovers, it’s the difference between self-satisfaction and consorting with someone you’re fond of. There is no question of which is better.

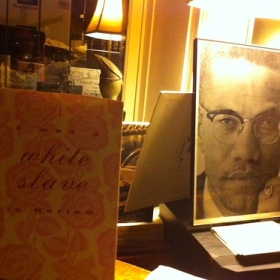

The electronic word is not the answer to a problem. The book in history has been an impediment only to the enemies of freedom. Civilized people distinguish themselves as People of the Book, principled by a voraciousness of truth electronic media is too flimsy to sustain. What makes its diminution a concern is, it sustains.

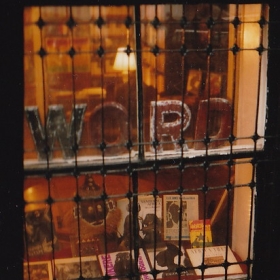

The fin-de-siècle’s greatest bubble is likely to be its’ technologizing itself into barbarism. As an antiquarian book dealer, for the past 36 years I’ve had a unique perspective on the change of consciousness responsible for the consequences of Post-Literacy resonating through our Culture. It’s been a front row seat to watch the demise of print autonomies I’d grown accustomed to, being defaced.

So I rant: The technological word is a new strain of the word virus. A consciousness clothed in an alphabet plays by different rules than one an aural-tactile vocabulary scantily attires. Wrought by the hand for the eye it can reproduce thoughts that can’t be seen, hidden wisdoms. Things are falling apart. Achebe’s novel by that near-same title illustrated the analogous consequences of literacy/modernity on a millennium old oral culture, rendering it, as I like to say, the stuff of nostalgia in two generations. Literacy precedes print culture by a mere five hundred years and print is now ceding its primacy as the receptacle of history to electronic media.

When someone asks, and they do here in the shop, I tell them: If you want to see where we’re going, look to Nigeria. Out of all of history, Nigeria will have been literate for about 60 years. Meaning, they got most of their information from printed sources. They have been Post-Literate since the end of their civil war in 1971. Meaning that they get most of their information from electrical sources.

I say we have been Post-Literate since September 11th, 2001. We’d been building up to it for a decade, since the introduction of the word processor and the internet. Since then most people here get their information electronically. It has effected a change of consciousness. We’ve a generation that’s known the internet from first consciousness and, trapped in a the web they’ve wove, can’t tell the real turtle soup from the mock.

What are we going to tell them? Beware of Maya? That it was just my imagination, running away with me? You’ve heard my rant haven’t you?

‘As the world turns, cultures that have survived print are finding themselves better immunized to the ill-effects of what linguists call Secondary Orality than we are. Secondary Orality is Post-Literacy. Its media is electronic. It is about pixilated pictures talking, it is immaterial; reality is topped by virtuality and apprehension betters comprehension.’ The electronic word has no substance. It is selling you nothing for something. Virtual is not acceptable. Electricity can be turned off.’

Which is not to say it has no place. It needs putting in its place. The electric book may be to the new millennium what the pocket paperback was to mid-century. In an orderly period of adjustment, as a print-borne liberal-humanist culture, we’d know better. What if something goes wrong? I thought librarians were getting beyond themselves when they let go of the card catalogues. My family and I lived within a mile of the World Trade Center and on 9.11 digital communications went down and stayed down for days. There was no cell phone, no tv, there was no internet. Shit happens.

I was preachin’ then: The Bible has it that to be human is to see reality “through a glass darkly.” We may even give literacy too much credit. For instance, romance is a literary construct invented by the troubadour poets in 14th-century France and is not native to the human condition. The damsel in this dress and the night with shining amour are constraining stereotypes when one’s accustomed to a society in which there are men who are daughters and where women have wives.

In Secondary Orality, the Oral world of the majority is in ascendance, as the literate world assumes the embattled mantle of Empire in the Age of Globalization. Ultimately this war, like all others, will be a racist war fought for money. In this war, the growing difference between the haves and the have-nots could transcend nationalist identities and assume the proportions of faith. In its re-empowerment, orality could revenge itself by assuming modernism’s destructivist methodology of tearing everything down and putting something different in its place. Things are not what they seem. We need to listen closely to what we don’t understand.’

Nostalgia? I don’t think so. Is Proust nostalgia? No. Too much of me is wrapped up in the literature, the users manuals for life. Literature contains the hallowed traditions, intellectual and artistic benchmarks of where I eat and sleep.