Marlon James’ views of a crime in ‘A Brief History of Seven Killings’

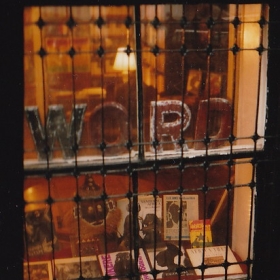

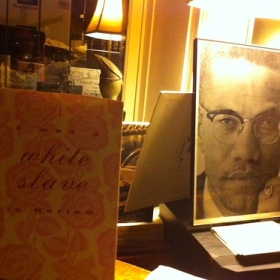

Photo by Carolyn Cole at Jumel Terrace Books. LA Times Review by By CAROLYN KELLOGG

Marlon James’ “A Brief History of Seven Killings,” is a thrilling, ambitious fictionalization of the assassination attempt on Bob Marley in 1976 and the afterlives of Marley’s would-be assassins.

Both intense and epic — it’s told in rapid-fire short chapters while clocking in at 704 pages — the novel is narrated by a huge cast of characters. There are patois-speaking street thugs, CIA operatives, Jamaican gang leaders, a magazine writer, a displeased ghost, an American hit man, and a woman who slept with the singer just that once.

“Truth keeps shifting,” James explains by Skype, sitting at his desk in St. Paul, Minn. “Five, six stories, even contradictory stories, can exist at the same time and they’re kind of all true and all false. There is no one story.”

Like Don Delillo’s “Libra,” a fictionalized version of the conspiracies around the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the book is awash in Cold War spies, desperate gunmen and oddball players. James’ novel, however, has more music, more sex, more brutal violence.

“‘Libra’ was definitely one of the books I was reading,” he acknowledges. “‘American Tabloid’ by James Ellroy — that was my textbook actually. I really wanted to stick closer to crime fiction than trying to write this literary novel. I probably failed at that,” he says, laughing.

The one character readers won’t find is Marley himself — in the book, he is called the Singer.

“I didn’t want to get into the whole ‘imagining in the mind of Marley,’ for artistic and lord knows legal reasons,” he says. “I was more fascinated with what was going on around him.”

He says he had a typical suburban childhood: “My upbringing was as ’70s as everybody else’s in the world. My parents were the first of this emerging middle class in Jamaica. Before you were either part of the planters or descendants of slaves working in fields. I grew up with two working parents, two cars, raised by watching the TV.”

James graduated from the University of the West Indies in 1991; a decade passed before he began writing. His first novel, “John Crow’s Devil,” was rejected dozens of times before finding a home with the independent Akashic Books, which published it in 2005; it was a Los Angeles Times Book Prize finalist.

“I consider myself a moralistic writer,” he says. While writing “A Brief History of Seven Killings,” he says, “I got really interested in the motives of people: What is unchecked ambition. Who really suffers from violence. How by trying to escape it, you sometimes run right back into the middle of it.”

The novel had a slow start. At first he tried to write it from the American hit man’s point of view, a character who wouldn’t understand the implications of his actions, but James got stuck. Another hundred pages from another character’s perspective didn’t work, either.

Frustrated, he told a playwright friend, “I don’t know whose novel this is; I can’t figure out whose story it is.” She replied, “Why do you think it’s one person’s story?”

That was the key. He immersed himself in novels with multiple first-person narrators — William Faulkner’s “As I Lay Dying” and “My Name Is Red” by Orhan Pamuk. Informed by the films of Robert Altman and the 1966 Esquire article “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” in which Gay Talese profiled Sinatra after having access to everyone in his circle but Sinatra, James constructed a novel with a cast of characters so huge it fills four pages at the front of the book.

“I wanted different degrees of distance, everybody from somebody who fired the shot to somebody who was just in the wrong place at the wrong time,” he says. As a child hearing of Marley’s shooting, he understood “if he could get shot, then anybody could be,” while now he sees the incident as “allegory — we’re descending into chaos in the country.”

In the U.S., James and his friends once made a pilgrimage to Prince’s house. The plan was to jump the fence, touch the first wall, then run out. “As we hit the gate sirens just went off, there was police everywhere,” he puts his hands in the air and raises his voice to a squeak. “We were like, ‘We’re English professors! We’re English professors!'”

“They were actually really nice, telling us about all the people coming all the time,” he continues. “Women with babies, men with vendettas, all come saying they have business with Prince.”

This is, in fact, exactly what the onetime lover of the Singer does in James’ novel: She waits outside his gate as if she might will another encounter, plead with him. Her singular voice, with relentless momentum and emotional switchbacks, is propulsive. “Nina Burgess just sort of came in and took over the book,” James says.

To manage the many characters and complex plot, he created charts and timelines. “I had to know what everybody was doing. Even if I don’t write about it, I need to know that Nina was making herself a cup of coffee while Josey Wales was killing this guy,” he explains. “You start to fill in non-narrative stuff that real people do. Like sleep, like boring stuff. That made them more real.”

What James constructed might be called an epic Jamaican novel, but that would be wrong: It’s simply epic.

*

On sale at Jumel Terrace Books.